I missed the train recently and it just so happens that a gorgeous indie bookstore is on down the road from the station, so what was I supposed to do? Wait for half an hour on the cold platform?

The problem is that I can’t visit No Alibis in South Belfast without buying something. I’ve tried. And even though I know this to be true, I still pop in with an innocent and deluded belief that, this time, I will leave empty handed. My TBR pile is teetering dangerously next to my bed, I remind myself. I don’t need more books, I think, as I step over the threshold. Ah, but look at them! All laid out with their beautiful covers nestling next to one another like old and new friends. One more wouldn’t hurt, would it?

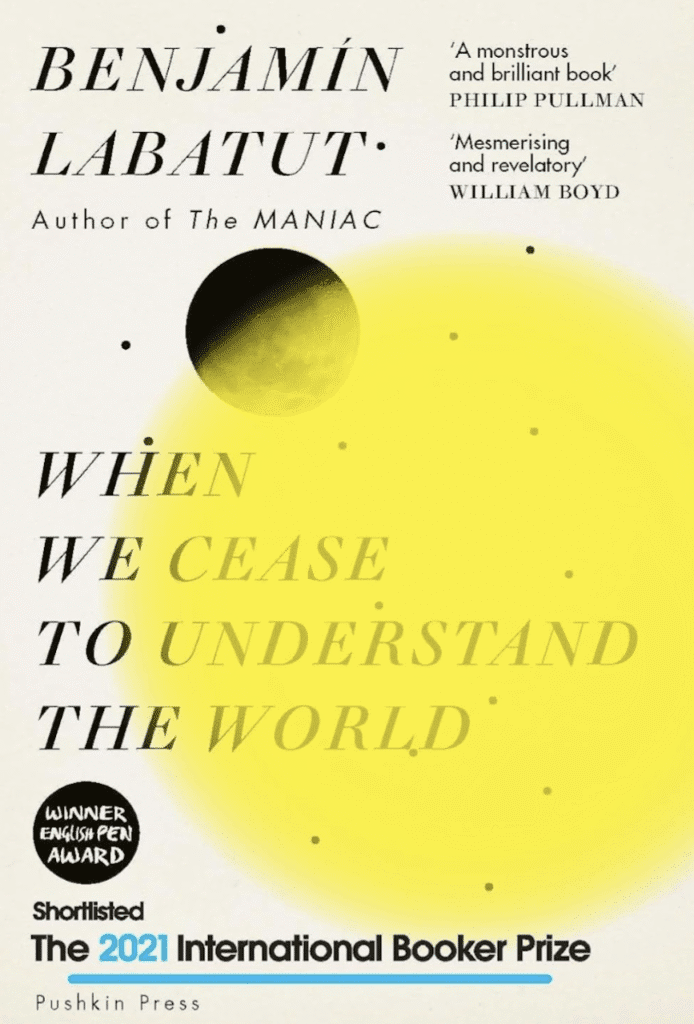

On this particular day I had been chatting with a friend about the state of the world (it’s awful) and how I don’t understand what’s happening. We parted with drooping shoulders and then I missed the train and got even more annoyed. So as I scanned the bookshelves (convinced I wasn’t going to buy anything) I could hardly believe the title of one of the staff recommendations. ‘When We Cease to Understand the World’ by Benjamin Labatut was shining like a beacon and telling me to pick it up so, with barely a glance at the blurb, I took it to the till. This would fix my philosophical failures, I thought, as I made my way to the station.

I started to read on the journey home and was immediately transfixed. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever read, sitting between non-fiction and fiction, and I ate it up in two days. It’s dystopian and frightening and weird and engrossing. My quantum mechanics aren’t great (who’s with me?) but there was Schrödinger and Heisenberg alongside Einstein and Oppenheimer as they make discoveries that reach forward into a bright future full of new knowledge and yet all the while they are putting our world (and the humans within it) at terrible risk. Somehow these characters are only half-alive, both real and fictitious. Parts of my mind opened up that had been long-closed (or perhaps had never opened).

In case it’s not obvious, I can’t really describe it, and the Booker Prize judges agree. It’s odd. When I set the book down I took a deep breath and did indeed feel a bit better about the world. Perspective in a crisis really helps and stepping back to look at the universe from afar makes my problems very small indeed.